|

| The Great Barry John laying waste to England |

Although the oil price shocks affected all industrialised economies inflation had a particularly severe impact on the UK, we quickly became known as the sick man of Europe. Our smoke stack industries were failing against new competitors and trades unions made it impossible for us to improve productivity; this labour intransigence forced unemployment to horrific levels. But worst of all, Inflation was in double digits eating up savings, wealth and security and against all the laws of Keynesian economics we had high inflation, high unemployment and high interest rates – stagflation! Like a creeping terminal disease it infected all parts of our economy and did untold social damage; many of today’s most potent social problems steam directly from this time – rising divorce rates, poor parenting, plunging standards in education, rising crime rates and so it goes on.

The specter of inflation remained a haunting presence right through the 1980s and well into the 1990s and we still have the ability to light the fire under prices in the UK; in 2009 Sterling was devalued by about 20% (concerns about the level of debt) and because of our dependence on imports prices rose sharply. In fact the UK has been the only major economy to suffer high inflation since the “great recession”. Today our inflation rate is exactly at the Bank of England target rate of 2% and with an economy growing at around 3% annually we are in “Goldilocks” territory.

If things all things are rose in the UK’s economic garden (actually there are some nasty pests lurking) the same cannot be said for the Eurozone. The big fear in Euro is for falling prices – deflation. Currently Eurozone inflation is running at about 0.8% and heading towards zero and negative territory, although there are wide differences with some southern European states already suffering from real deflation.

On the face of it deflation sounds quite appealing – we all enjoy the Christmas sale period when old stock is sold off cheaply, so why is every so exercised about the threat of deflation? The primary reason is that there is some recent history – in 1990 Japan’s was the most prosperous nation of earth its telephone company NTT was valued above the whole of the London Stock Exchange; but then came the bust. Since 1990 Japan has suffered 25 years of declining living standards, low or no growth and strong deflationary pressure. Japan has been trying to escape the deflation death spiral for 20 or more years, without much luck and no one in Europe is keen to follow suit. So what are the main problems with deflation?

First of all deflation is really a symptom of falling demand (depressed prices) but also once it takes hold there is never a good time to go on a spending spree as a result spending and specifically borrowing falls away. If cash is rising in value it’s difficult to make the case for investment, this springs a nasty liquidity trap where the lack of borrowing triggers further deflation and saving – destroying future demand and growth.

Next up is the plight of borrowers, if savers are in heaven borrows are in hell as they have the problem of dealing with both the interest on the money they have borrowed and the fact that money itself is worth more, the rising value of money pushes up the real cost of borrowing. This creates another spiral of deflationary death – deflation leads to lower borrowing, which leads to low economic activity and productivity which reduces the value of labour driving down salaries (and probably living standards), which promotes further deflation.

The textbook answer to dealing with deflation is to reduce interest rates to a point where equilibrium is restored so the savers want to lend, investors want to borrow, demand ensures scarcity and all of these restore us to an inflationary course. The problem is that we are now at the lower bound of interest rates (they can’t go lower than zero – or can they) as interest rates are at 0.25% in the Eurozone. Worse still there are some global pressures that may force the pace of deflation. The recent crisis in emerging markets, prompted by the ending of QE by the Fed, has sharply lower currency values in some emerging markets, this means imports will become cheaper for Europe and also exporting will become more difficult – another deflationary death spiral.

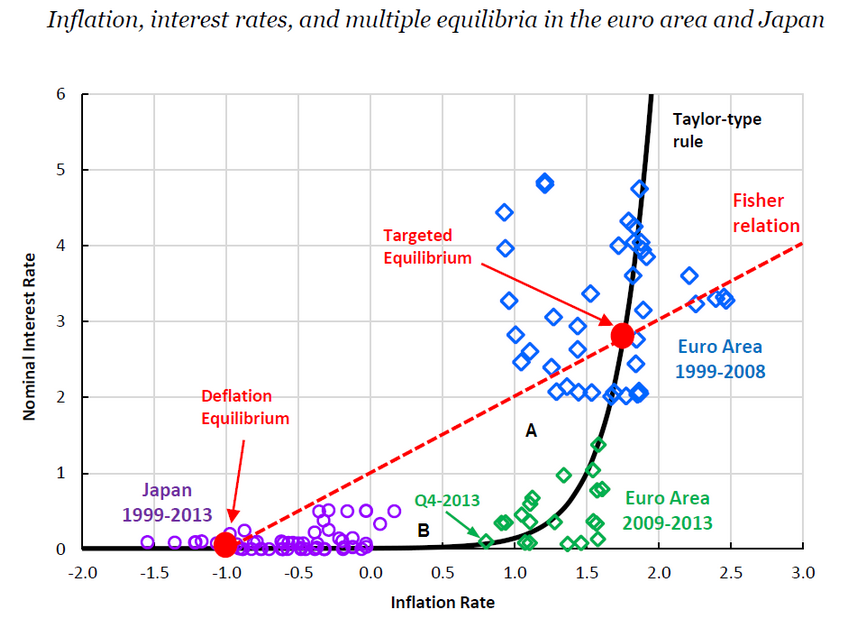

It's probable that Europe could find itself (like Japan has) in a “Deflationary equilibrium” this is where at zero interest rates we have falling prices and very high unemployment. A kind of Stagdeflation. Gavyn Davis has a great graph that could confuse anyone but it basically show how the Eurozone is slipping towards the territory Japan has occupied for the last 15 years.

The target equilibrium, should balance interest rate with full employment or at the “natural rate” of employment. Clearly as the point of equilibrium moves toward the X axis the natural rate of employment is at a level of high unemployment! On today’s number of 0.8% the Eurozone is somewhere between points A and B on the chart – not a good place to be. If one looked in detail at different states, some: Greece, Portugal and Spain would already be at point B! All very worrying.

When I was looking at this chart there was also something else that leaped off the page, perhaps you noticed as well. The Japanese data spans 15 years and the interest rates barely move – stuck between 0 and 0.5%, and the inflation rate fluctuates in a narrow band from -1.5% to 0.3%. The thing that’s niggling away at the back of my mind is - that after a period of time negative real interest rates might just become the problem? This goes against most (all) economics teaching – either Keynesian or Monetarist.

So why might this be, you would have thought that negative real interest rates would be a great stimulus to economic activity and therefore inflation. But is it possible that after a protracted period of low rates other rational behaviours could kick in? in fact these behavious are embedded in the first deflationary death spiral I mentioned – once money is consistently decreasing in value the appetite to invest or to leverage-up must drain away, if my mortgage costs are half what they were 5 years ago why risk a change of career or starting a new business, there is no driver (Hunger) for me to change what I am doing. For the middle classes and for many businesses the status quo is not too painful, it may not be exciting but it’s good enough. So how do we break the cycle – well we could raise interest rates to raise the level of “hunger” in working people and to deal with all those Zombie business that are using up resources (people and capital). This contrarian move would also have the effect of increasing the value of the currency forcing businesses to become more efficient. The problem is that these “initiatives” would also drive up unemployment, suck in exports and make things noticeably more painful, the quid pro quo however would be the raised appetite for risk - Hunger Games.

The question is whether the positives of structural change would out-weight the damage to employment levels; my guess it would be a close call in an independent economy such as the UK. Economies tend to recovery quickly from the short sharp shock of very high interest rate – take the UK economy in 1992 when rates were lifted to over 15% - this initiated the longest economic up-turn in our recent history. The problem in Europe is that the single currency makes all this impossible – so they have to sit back in their self-inflicted torpor and dream of the Hunger Games.

No comments:

Post a Comment